Welcome to The Fracturing of Virtue

Essays on the State of the American Body Politic

Many years ago, when I was a much younger man, I made it my practice to siphon off a meager portion of my paltry teacher’s salary to pay for a subscription to a monthly book club featuring classical editions of what were then known as The Great Books (I’m not sure they’re even called that anymore). Each month, a beautiful book arrived on my doorstep prompting me to quickly open the package to admire each book showcasing luxurious leather binding and gilded edged pages.

Usually a classic work of Shakespeare, Plutarch, or Montaigne, or some other vaguely familiar author of note, those books quickened my pulse even though, secretly, I knew all too well that I likely would never find time in my busy young life to read them. I suppose I thought of them as a good investment or perhaps I felt that having such books in my home was a sign of my fealty to an intellectual life. In that moment of self-righteous arrogance, it was as if I had found one more piece of armor to shield me against the onslaught of the barbarians whom I was convinced were approaching the gate. Truth be told, proudly displaying them in my lonely writer’s garret and carefully arranging them on my homemade shelves of boards and blocks made me feel smart, very smart. They were as much furniture as they were books as I rarely cracked a page.

I have only recently rediscovered them in the serenity of my older, retired life and now, much better read and very well educated, I have the time and intellectual mettle enough to pore over them. I am in the autumn of my life now, and having completed a Ph.D. at a fine university some twenty two years ago, this collection is my humble attempt to return to the intellectual pursuits of my younger years; the ones before the busy days bursting with the obligations of family, building a career, and earning a living. Back then I reconciled myself to the fact that I had likely missed the speeding train of scholarship and the intellectual life. But, by way of a lifetime of experience along with my journey through a maze of universities as both student and professor, these essays, and my reader’s indulgence, might just allow me to catch a late train back.

The following then, is a collection of essays entitled The Fracturing of Virtue and are designed to provoke individual self-reflection about the citizen’s role as just one part of a larger national whole, a sort of do it yourself Gestalt program. No one can deny that in these troubling times, one is forced to agree with Jill LePore in her seminal work, These Truths, A History of the United States, that “The United States is founded on a set of ideas, but Americans have become so divided that they no longer agree, if they ever did, about what those ideas are, or were."

Each essay will present a topical examination of the general argument that, as citizens of our republic and especially in light of more recent events, we have an obligation, more a duty, to step back from our personal politics and ask ourselves a series of questions: Is this the nation we want to be? Is this how we will treat our fellow Americans and how we want to be treated? Have we finally and irrevocably reached the end of our belief in the quest for a more perfect union? Most importantly, can we find our way back to the center, back to a place where, in the words of Utah governor, Spencer Cox, following the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk, we need to disagree better.

At the same time and while reeling from the toxic state of our current politics and yet another shooting of a public figure, I couldn’t help but ask even more questions. What happened to all the good people? Where did all this hate and avarice come from? When did we become so much more about I instead of We? When did we become so callous and unfeeling about the plight and pain of others? How did we become a nation of I got mine and too bad for you? How did we get here and can we ever find the road back to kinder, gentler America?

Sadly, I’m not so sure that road is open any more. It seems that we have been traveling on a detour for quite some time. Our history tells us that this political/cultural crisis is nothing new but somehow, looking back, I always kept faith that no matter what, we’d be ok. We’d find our way back to the center. Now, I am plagued by doubt. My hope is that by way of these essays and the conversation they will provoke, a cautious optimism that we still can may just emerge.

As a matter of full disclosure, I do want the reader to know that my essays do not pretend to be scholarship but where appropriate, I will cite sources. Nor are these essays intended to be declarations of absolute certainty. We are living in increasingly dark, dangerous, and unprecedented times and anyone who clings to that kind of self-righteous certainty will be disappointed. That said, my essays are formed on the premise that, despite my passion, I will always strive to believe that those who disagree with me, those who oppose my point view, no matter how strident, just might be right.

Part of what accelerated my thoughts on this subject resulted from my reading of Tom Ricks’ excellent book, First Principles, What America's Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country. I read it twice because it’s that important for gaining an understanding of how far from virtue we have strayed. Ricks thoroughly examines the classical forces that shaped the thinking of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and James Madison before and during the birth of our republic. Along with some honest criticism, he focuses on each of these giants of the American Pantheon and the extent to which the influence of the classic Greeks and Romans helped to shape their documents, our documents, that gave birth to our nation. Among other traits, he ruminates on the idea of virtue and it’s amidst that discussion that these essays came to be.

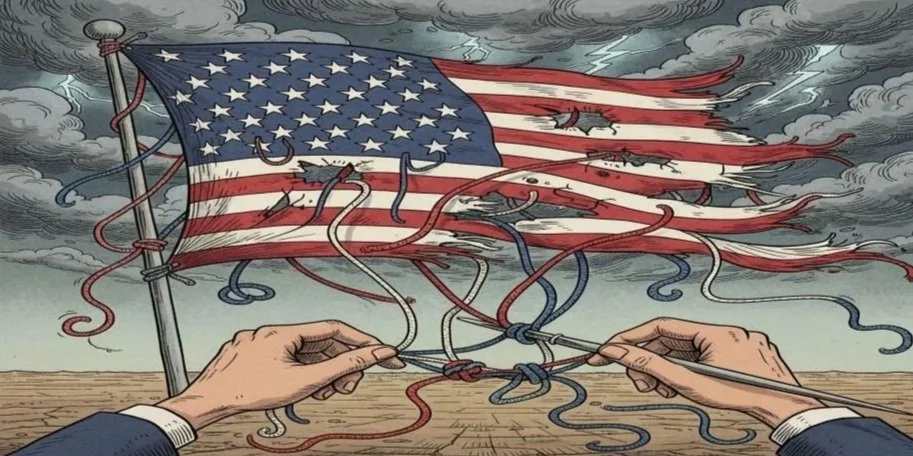

The most recent rendition of this collection of essays began just about the time the current president surprised the world with his second victory. Amidst the rancor of that campaign, the election and certainly since then, it became apparent to me, a lifelong student and professor of politics, government, and history, that something had fundamentally changed. Like the lyrics of a musical remnant of my college years, there was most definitely something happening here. It somehow feels different than any other era of modern American political history. Even during the caustic debate and division of the Vietnam War and the decades long struggle for civil rights, there at least remained some threads of the belief in what Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger called the vital center of American political discourse; the idea that our democracy depended on our determination to sort through all the rancor and find our way back to compromise and see politics as the art of the possible. But today, it seems that the threads of the American fabric are ever more frayed and amidst the phenomenon of Trump 1 and now Trump 2, that fabric threatens to completely unravel.

Almost ten years later and coming out of our most recent contentious election, it could easily be argued that not since the Civil War have we been so far from Schlesinger’s vital center. In a conversation with a colleague concerning the recent election turmoil, I commented that it seemed to me that too many Americans now define their role in the American political process in a very simple formulaic statement. If it benefits me, I’m for it. If it negatively affects me, I’m opposed to it. And, if it does neither, I don’t give a damn. As I considered those words, I realized that I may have just offered up the obituary of the idea of the common good, maybe even the beginning of the demise of American democracy itself. More than other point in in all my seventy three years, I was now truly concerned that the American Project might be in real jeopardy.

As I continued to reflect on the polarization that characterizes out political discourse, I paused to consider the mariners of ancient Greece who embarked on a journey of exploration knowing full well that their journey would include great darkness and danger. They went anyway. So it is with us. We cannot turn back. We must not be afraid.

In the epic film, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, the character Sam attempts to explain to his companion Mr. Frodo, why the struggle to save Middle Earth must continue. The comparison to our current national struggle is fairly obvious.

Frodo: I can’t do this, Sam.

Sam: I know. It’s all wrong. By rights we shouldn’t even be here. But we are. It’s like in the great stories, Mr. Frodo. The ones that really mattered. Full of darkness and danger, they were. And sometimes you didn’t want to know the end. Because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end, it’s only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come. And when the sun shines it will shine out the clearer. Those were the stories that stayed with you. That meant something, even if you were too small to understand why. But I think, Mr. Frodo, I do understand. I know now. Folk in those stories had lots of chances of turning back, only they didn’t. They kept going. Because they were holding on to something.

Frodo: What are we holding on to, Sam?

Sam: That there’s some good in this world, Mr. Frodo… and it’s worth fighting for.

At the young age of twenty eight in his Lyceum address, Abraham Lincoln also warned us. "If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide."

Being an American historian of a particularly romantic bent, I have to believe that the answers to our divided body politic are more likely found in the hearts and minds of average Americans rather than those of the chattering political class. Winston Churchill is said to have remarked that “Americans can always be trusted to do the right thing, once all other possibilities have been exhausted.” If he is correct and our history is any indication, my faith in the American people to do the right thing in the end remains a fairly safe bet.

This introductory essay is the first in a series. My intent is to post an essay each month and I trust you will find value in the words that I write. Most of all, I truly hope they spark conversations with neighbors, family, friends, and even those not so friendly. Through reasoned argument, dialogue, and “disagreeing better,” perhaps we can take the first steps to repairing the fracturing of our virtue and in doing so, remembering Benjamin Franklin’s admonishment to Elizabeth Willing Powell, who asked him outside the Constitutional Convention in 1787, “Dr. Franklin, what kind of government do we have?,” to which he allegedly replied, “A republic Madam, if you can keep it.”

Let The Conversation Begin